TAZ: Miss Karemich, “No teeth? Up to 450 blue helmet soldiers were placed in the Eastern Bosnian small town to protect the civilian population. Nevertheless, during the week of July 11, the Serbian units were able to choose their victims before the gates of the UN position at that time, and more than 8,000 bosnias killed them in Srebrenitsa. A photograph of the graffiti of the soldier hid them for one of their works of art with self -confident. What is the story behind your work “Bosnian girl”?

Shezhla Karemich: At that time, photographer Tarik Samara showed me his photos from the cut. For several years, he documented the surviving genocide, the exhumation of mass graves, the identification of victims and their repeated appetizer. One of his photographs shows the graffiti, who left the UN soldier, who was placed in the slender during the war. The message of this graffiti deeply moved me. She met me at a personal level. I turned them into a poster along with a portrait that recorded a tariff. I wanted to show this in the public space on the street – intentionally without the participation of other people or institutions. I did not want to convey the burden of this message to others, I wanted to wear it myself. This was before there were social networks in the form of how we learn about it today. Nevertheless, the “Bosnian girl” became almost immediately known thanks to newspaper advertising, postcards and posters. I contacted various media dominates and asked them to publish a picture – and everyone followed this request. However, there was also confusion and criticism. When the Bosnian Girl posts appeared on the streets of Sarajevo on July 11, 2003, some people were shocked. The US message in Bosnia ordered all the posters to be removed next to the message. But the most important point for me was the fact that the mother of the cuts were identified with the picture.

Taz: Mothers of Slabenitsa is an union of several thousand women whose relatives were killed in the genocide of the hub. They argued for decades for the criminal prosecution of criminals and for decent memorization. In addition, the association first sued the Dutch state in 2007 for damage. The photograph shows how some of them hold the image “Bosnian girl” in front of the office of the Prime Minister of Dutch. How did you notice this moment?

KARARICH: For me, this meant that I was successful: my body became a universal representation of the victim that refused to be a victim.

In an interview: Sejla kamerić

Visual artist Born in the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo in 1976.

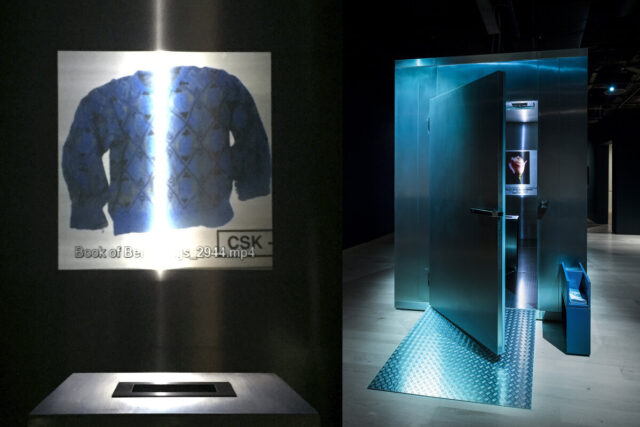

Their work Turn on the film, photography, installation and textile art. The motives of their art are personal memory and collective trauma. The seriousness of your topics often contradicts your light aesthetics and delicate materials.

Kamarich participates in exhibitions around the world For example, in Tate Modern in London or Musée d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

TAZ: What role does appropriate in your work play from the body, identity, memory?

KARARICH: For almost 30 years, I have used art as a means of communication, self -pollinating work and self -reflection -and, of course, also to reflect the world around me. Art is a continuous protocol that creates a space for understanding various points of view, form new identities – or free from those that were imposed on us from the outside.

Shezhla Karemich in front of his poster “Bosnian girl”

Photo:

Hamza Kulenovich

Taz: Participants responsible for the genocide cuts were a lot and covered a lot. After the murders, the Serbian units again bought corpses again, distributed mortals remain several mass graves to mask crimes. To date, the remains of more than 1000 victims are absent. In his work “The Medical Archive: from one study of all” in cooperation with ICMP (the International Commission for the loss of a person) and the memorial center of the cuts, create methods of forensic science by tangible.

KARARICH: I do not want to talk about polarized historical truths, but about scientific truth. History should be considered as a scientific discipline. This allows us to rely on undeniable facts and get a real understanding of what happened. One of my tasks was to make a large number of different data – evidence, indications, pictures, maps and legal documents – and translate them into an art form. For three years, I worked closely with 20 researchers to scientifically study all the judicial evidence of the war.

TAZ: Isn’t it too many arts asking for historical truths to be conveyed?

KARARICH: Art should not bear this responsibility. Justice and politics should deal with facts so that art can be free to ask questions and find new answers. At a time when moral and ethical values are destroyed, we must admit that the judiciary and politics must fulfill their roles. The works of art should have a place for different answers, for answers that may change over time. Facts next to him, and science enters here. Art should never undermine the importance of science – and vice versa.

TAZ: How do you approach as an artist in the topic of genocide, which carries such deeply long individual and collective wounds?

KARARICH: The genocide of the holes is captured by art. At the beginning of my career, when I created the “Bosnian girl”, my work was closely connected with my emotions and was primarily based on personal experience. It was about topics such as war, loss, movement and sexualized violence. Over time, I went through the healing process – through therapy and my own artistic practice. This allowed me to wear my emotions in the outside world. This put me in a privileged position with which I could begin to reflect on the stories of others in a new one.

TAZ: How can history reflect in art?

KARARICH: Historically, art always stood for the complex emotions that we are faced with an injury. Each work of art that arises from pain and injuries, just like our argument with him, helps us to cope with it, whether it is individually or collective. At the same time, it is important to admit that healing is never an obligation of art. Art is a wonderful tool for everyone. But as soon as art is politicized, it loses its strength, because it loses freedom. Today they often forget that art primarily means freedom: freedom to express itself and freedom to live freely – is released from power structures. One of the most valuable human skills is the creation of art and enjoy them.