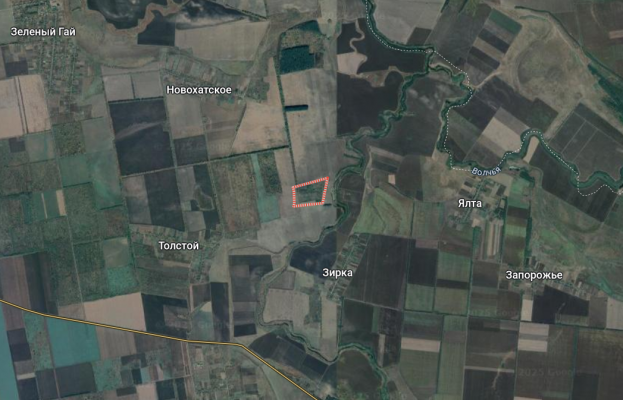

A shocking warning 6 years ago .. A simple malfunction killed 260 people! (Video+ photos)

The initial report of the Indian Directorate for the investigation of aircraft showed that in December 2018, the Federal Aviation Administration warned that some Boeing 737 aircraft contained incorrect fuel keys included in violation of its blocking function, which makes it vulnerable to unintentional movement, which can lead to stopping the engines during the flight. … Read more